Telco 2.0™ Research

The Future Of Telecoms And How To Get There

The Future Of Telecoms And How To Get There

|

Summary: Facebook has changed substantially since we first analysed the company in 2011. In our latest major report we explore the accuracy of our 2011 predictions regarding users, revenue and strategy. We also examine Facebook's current aspirations and challenges and explain why, where and how operators should be working with Facebook to build value. (March 2015, Dealing with Disruption Stream) |

|

Below is an extract from this 50 page Telco 2.0 Report (including a concise Executive Summary) that can be downloaded in full in PDF format by members of the Dealing with Disruption Stream here.

For more on any of these services, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

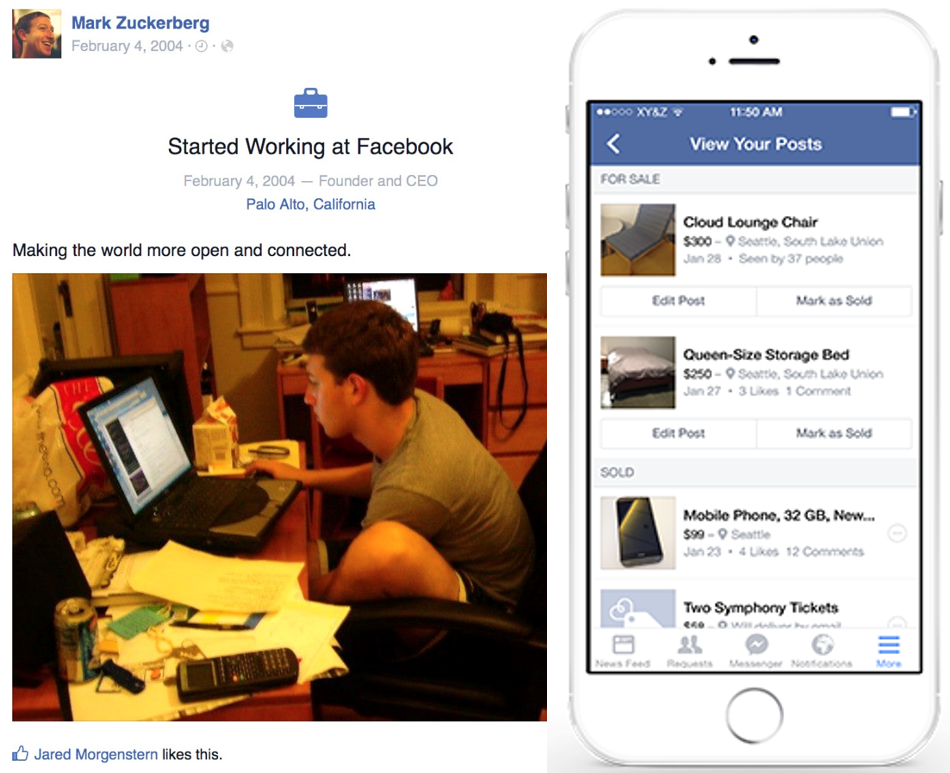

One of the things that sets Facebook apart from its largely defunct predecessors, such as MySpace, Geocities and Friends Reunited, is its ability to adapt to the evolution of the Internet and consumer behaviour. In its decade-long history, Facebook has evolved from a text-heavy, PC-based experience used by American students into a world-leading digital communications and commerce platform used by people of all ages. The basic student matchmaking service Zuckerberg and his fellow Harvard students created in 2004 now matches buyers and sellers in competition with Google, Amazon and eBay (see Figure 1).

Source: Zuckerberg’s Facebook page and Facebook investor relations

Launched in early 2004, Facebook initially served as a relatively basic directory with photos and limited communications functionality for Harvard students only. In the spring of 2004, it began to expand to other universities, supported by seed funding from Peter Thiel (co-founder of Paypal). In September 2005, Facebook was opened up to the employees of some technology companies, including Apple and Microsoft. By the end of 2005, it had reached five million users.

Accel Partners invested US$12.7 million in the company in May 2005 and Greylock Partners and others followed this up with another US$27.5 million in March 2006. The additional investment enabled Facebook to expand rapidly. During 2006, it added the hugely popular newsfeed and the share functions and opened up the registration process to anyone. By December 2006, Facebook had 12 million users.

The Facebook Platform was launched in 2007, enabling affiliate sites and developers to interact and create applications for the social network. In a far-sighted move, Microsoft invested US$240 million in October 2007, taking a 1.6% stake and valuing Facebook at US$15 billion. By August 2008, Facebook had 100 million users.

Achieving the 100 million user milestone appears to have given Facebook ‘critical mass’ because at that point growth accelerated dramatically. The company doubled its user base to 200 million in nine months (May 2009) and has continued to grow at a similar rate since then.

As usage continue to grow rapidly, it was increasingly clear that Facebook could erode Google’s dominant position in the Internet advertising market. In June 2011, Google launched the Google + social network – the latest move in a series of efforts by the search giant to weaken Facebook’s dominance of the social networking market. But, like its predecessors, Google+ has had little impact on Facebook.

2012-2013 – the paranoid years

Although Facebook shrugged off the challenge from Google+, the rapid rise of the mobile Internet did cause the social network to wobble in 2012. The service, which had been designed for use on desktop PCs, didn’t work so well on mobile devices, both in terms of providing a compelling user experience and achieving monetisation. Realising Facebook could be disrupted by the rise of the mobile Internet, Zuckerberg belatedly called a mass staff meeting and announced a “mobile first” strategy in early 2012.

In an IPO filing in February 2012, Facebook acknowledged it wasn’t sure it could effectively monetize mobile usage without alienating users. "Growth in use of Facebook through our mobile products, where we do not currently display ads, as a substitute for use on personal computers may negatively affect our revenue and financial results," it duly noted in the filing.

Although usage of Facebook continued to rise on both the desktop and the mobile, there was increasing speculation that it could be superseded by a more mobile-friendly service, such as fast-growing photo-sharing service Instagram. Zuckerberg’s reaction was to buy Instagram for US$1 billion in April 2012 (a bargain compared with the $21 billion plus Facebook paid for WhatsApp less than two years later).

Moreover, Facebook did figure out how to monetise its mobile usage. Cautiously at first, it began embedding adverts into consumers’ newsfeeds, so that they were difficult to ignore. Although Facebook and some commentators worried that consumers would find these adverts annoying, the newsfeed ads have proven to be highly effective and Facebook continued to grow. In October 2012, now a public company, Facebook triumphantly announced it had one billion active users, with 604 million of them using the mobile site.

Even so, Facebook spent much of 2013 tinkering and experimenting with changes to the user experience. For example, it altered the design of the newsfeed making the images bigger and adding in new features. But some commentators complained that the changes made the site more complicated and confusing, rather than simplifying it for mobile users equipped with a relatively small screen. In April 2013, Facebook tried a different tack, launching Facebook Home, a user interface layer for Android-compatible phones that provides a replacement home screen.

And Zuckerberg continued to worry about upstart mobile-orientated competitors. In November 2013, a number of news outlets reported that Facebook offered to buy Snapchat, which enables users to send messages that disappear after a set period, for US$3 billion. But the offer was turned down.

A few months later, Facebook announced it was acquiring the popular mobile messaging app WhatsApp for what amounted to more than US$21 billion at the time of completion.

In 2014 – going on the offensive

By acquiring WhatsApp at great expense, Facebook alleviated immediate concerns that the social network could be dislodged by another disruptor, freeing up Zuckerberg to turn his attention to new technologies and new markets. The acquisition also put to rest investors’ immediate fears that Facebook could be superseded by a more fashionable, dedicated mobile service, pushing up the share price (see the section on Facebook’s valuation). In May 2014, Facebook wrong-footed many industry watchers and some of its rivals by announcing it had agreed to acquire Oculus VR, Inc., a leading virtual reality company, for US$2 billion in cash and stock.

Zuckerberg has since described the WhatsApp and Oculus acquisitions as “big bets on the next generation of communication and computing platforms.” And Facebook is also investing heavily in organic expansion, increasing its headcount by 45% in 2014, while opening another data center in Altoona, Iowa.

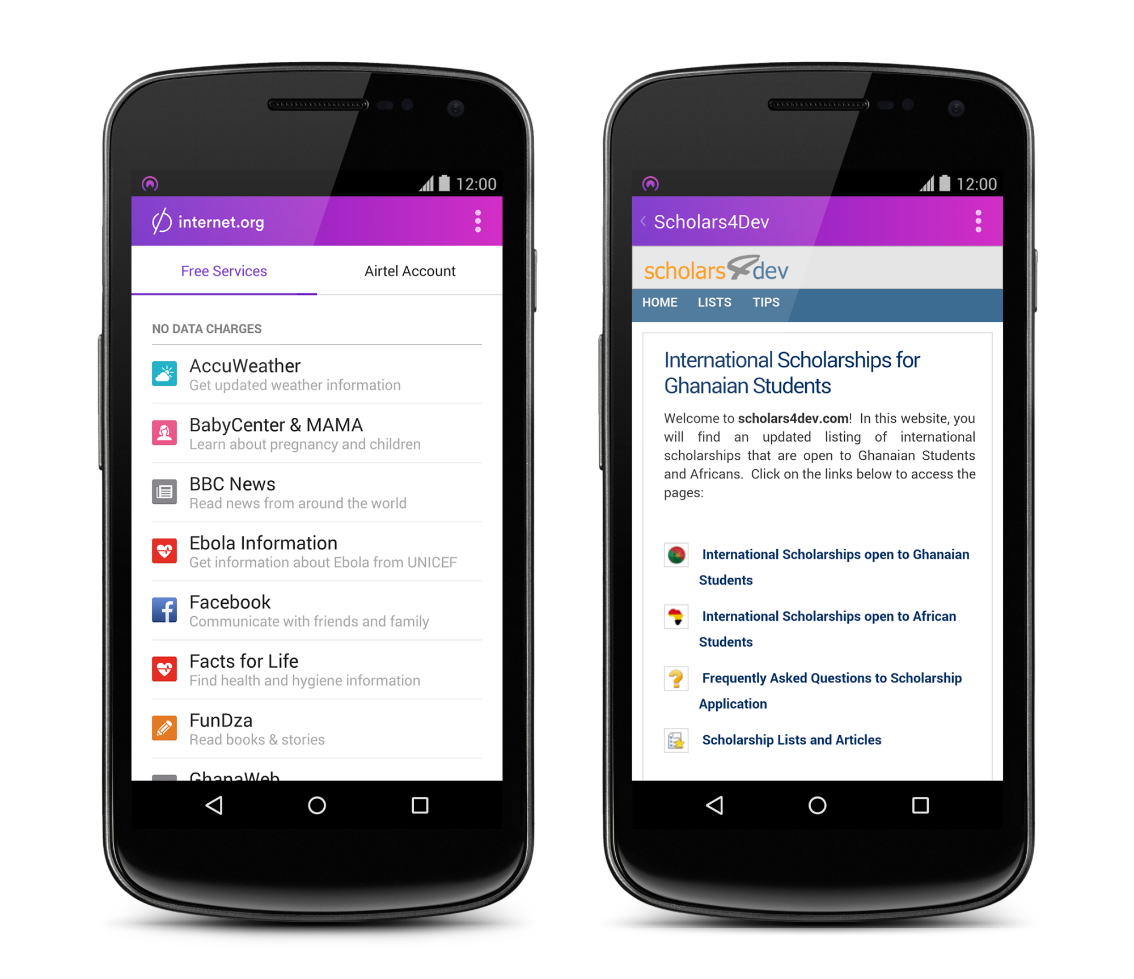

Zuckerberg also continues to devote time and attention to Internet.org, a multi-company initiative to bring free basic Internet services to people who aren’t connected. Announced in August 2013, Internet.org has since launched free basic internet services in six developing countries. For example, in February 2015, Facebook and Reliance Communications launched Internet.org in India. As a result, Reliance customers in six Indian states (Tamil Nadu, Mahararashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Kerala, and Telangana) now have access to about 40 services ranging from news, maternal health, travel, local jobs, sports, communication, and local government information.

Zuckerberg said that more than 150 million people now have the option to connect to the internet using Internet.org, and the initiative had, so far, succeeded in connecting seven million people to the internet who didn’t before have access. “2015 is going to be an important year for our long term plans,” he noted.

Although it is now listed, Facebook is clearly not a typical public company. Its massive lead in the social networking market has given it an unusual degree of freedom. Zuckerberg has a controlling stake in the social network (he is able to exercise voting rights with respect to a majority of the voting power of the outstanding capital stock) and the self-confidence to ignore any grumblings on Wall Street. Facebook is able to make acquisitions most other companies couldn’t contemplate and can continue to put Zuckerberg’s long-term objectives ahead of those of short-term shareholders. Like Amazon, Facebook frequently reminds investors that it isn’t trying to maximise short-term profitability. And unlike Amazon, Facebook may not even be trying to maximize long-term profitability.

On Facebook’s quarterly earning calls, Zuckerberg likes to talk about Facebook’s broad, long-term aims, without explaining clearly how fulfilling these objectives will make the company money. “In the next decade, Facebook is focused on our mission to connect the entire world, welcoming billions of people to our community and connecting many more people to the internet through Internet.org (see Figure 2),” he said in the January 2015 earnings call. “Similar to our transition to mobile over the last couple of years, now we want to really focus on serving everyone in the world.”

Source: Facebook.com

Not all of the company’s investors are entirely comfortable with this mission. On that earnings call, one analyst asked Zuckerberg: “Mark, I think during your remarks in every earnings call, you talk to your investors for a considerable amount of time about Facebook's efforts to connect the world, and specifically about Internet.org which suggest you think this is important to investors. Can you clarify why you think this matters to investors?”

Zuckerberg’s response: “It matters to the kind of investors that we want to have, because we are really a mission-focused company. We wake up every day and make decisions because we want to help connect the world. That's what we're doing here.

“Part of the subtext of your question is that, yes, if we were only focused on making money, we might put all of our energy on just increasing ads to people in the US and the other most developed countries. But that's not the only thing that we care about here.

“I do think that over the long term, that focusing on helping connect everyone will be a good business opportunity for us, as well. We may not be able to tell you exactly how many years that's going to happen in. But as these countries get more connected, the economies grow, the ad markets grow, and if Facebook and the other services in our community, or the number one, and number two, three, four, five services that people are using, then over time we will be compensated for some of the value that we've provided. This is why we're here. We're here because our mission is to connect the world. I just think it's really important that investors know that.”

Takeaways

Facebook may be a public company, but it doesn’t worry much about shareholders’ short-term aspirations. It often behaves like a private company that is focused first and foremost on fulfilling the goals of its founder. It is clear Zuckerberg is playing the long game. But it isn’t clear what yardsticks he is using to measure success. Although Zuckerberg knows Facebook needs to be profitable enough to ensure investors’ continued support, his primary goal may be to bring hundreds of millions more people online and secure his place in posterity. There is a danger that Zuckerberg’s focus on connecting people in Africa and developing Asia means that there won’t be sufficient top management attention on the multi-faceted digital commerce struggle with Google in North America and Western Europe.

Network effects still strong

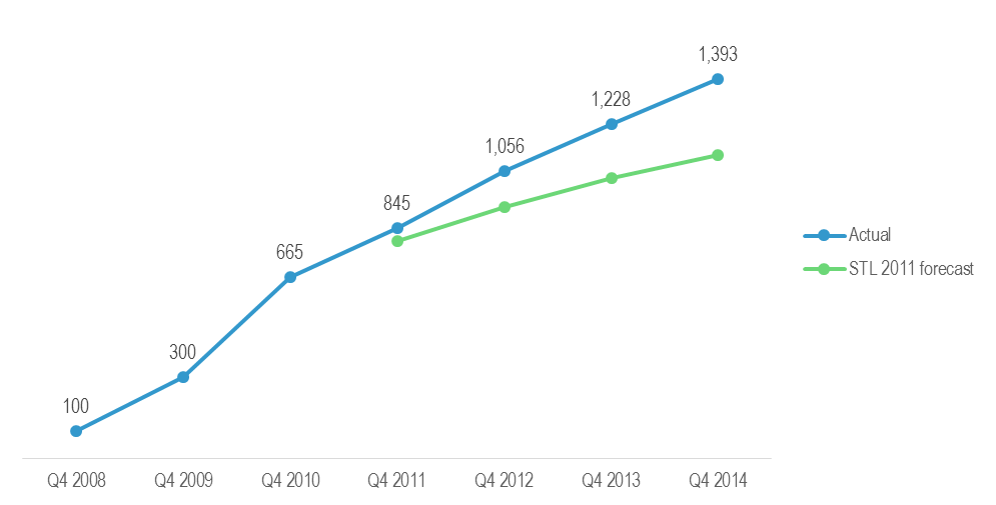

Within that wider mission to connect the world, Facebook continues to do a great job of connecting people to Facebook. Fuelled by network effects, Facebook says that 1.39 billion people now use Facebook each month (see Figure 3) and 890 million people use the service daily, an increase of 165 million monthly active users and 133 million daily active users in 2014. In developed markets, many consumers use Facebook as a primary medium for communications, relying on it to send messages, organize events and relay their news. As a result, in parts of Europe and North America, adults without a Facebook account are increasingly considered eccentric.

Source: Facebook and STL Partners analysis

Having said that, some active users are clearly more active and valuable than others. In a regulatory filing, Facebook admits that some active users may, in fact, be bots: “Some of our metrics have also been affected by applications on certain mobile devices that automatically contact our servers for regular updates with no user action involved, and this activity can cause our system to count the user associated with such a device as an active user on the day such contact occurs. The impact of this automatic activity on our metrics varied by geography because mobile usage varies in different regions of the world.”

This automatic polling of Facebook’s servers by mobile devices makes it difficult to judge the true value of the social network’s user base. Anecdotal evidence suggests many people with Facebook profiles are kept active on Facebook primarily by their smartphone apps, rather than because they are actively choosing to use the service. Still, Facebook would argue that these people are seeing the notifications on their mobile devices and are, therefore, at least partially engaged.

...and the following report figures...

...Members of the Dealing with Disruption Stream can download the full 50 page report in PDF format here. Non Members, please subscribe here. For other enquiries, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

Technologies and industry terms referenced include: Facebook, Google, strategy, telecoms, Android, commerce, Connect, Apple, Zynga, wearables, partnership, Youtube, disruption, innovation.