|

Summary: Cable operators are on the verge of a massive and remarkably easy capacity upgrade. Where it has begun, fixed incumbents are already being forced to deploy fibre. Gigabit WiFi is coming too, so mobile operators are very much concerned. (May 2015, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Network Stream.) |

|

Below is an extract from this 14 page Telco 2.0 Report that can be downloaded in full in PDF format by members of the Executive Briefing Service and Future of the Network Stream here.

For more on any of these services, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

Since at least May, 2014 and the Triple Play in the USA Executive Briefing, we have been warning that the cable industry’s continuous improvement of its DOCSIS 3 technology threatens fixed operators with a succession of relatively cheap (in terms of CAPEX) but dramatic speed jumps. Gigabit chipsets have been available for some time, with the actual timing of the roll-out being therefore set by cable operators’ commercial choices.

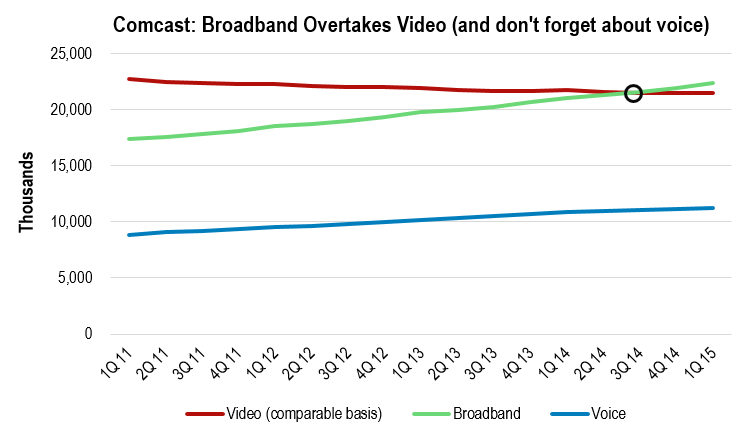

With the arrival of DOCSIS 3.1, multi-gigabit cable has also become available. As a result, cable operators have become the best value providers in the broadband mass markets: typically, we found in the Triple Play briefing, they were the cheapest in terms of price/megabit in the most common speed tiers, at the time between 50 and 100Mbps. They were sometimes also the leaders for outright speed, and this has had an effect. In Q3 2014, for the first time, Comcast had more high-speed Internet subscribers than it had TV subscribers, on a comparable basis. Furthermore, in Europe, cable industry revenues grew 4.6% in 2014 while the TV component grew 1.8%. In other words, cable operators are now broadband operators above all.

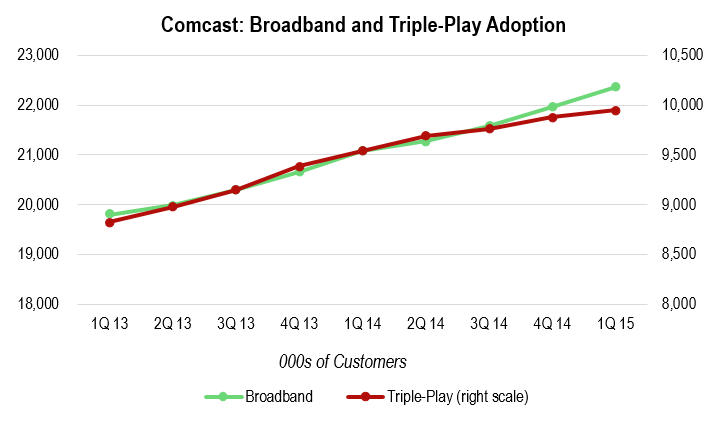

Source: STL Partners, Comcast Q1 2015 trending schedule

In the December, 2014 Will AT&T shed copper, fibre-up, or buy more content - and what are the lessons? Executive Briefing, we covered the impact on AT&T’s consumer wireline business, and pointed out that its strategy of concentrating on content as opposed to broadband has not really delivered. In the context of ever more competition from streaming video, it was necessary to have an outstanding broadband product before trying to add content revenues. This was something which their DSL infrastructure couldn’t deliver in the context of cable or fibre competitors. The cable competition concentrated on winning whole households’ spending with broadband, with content as an upsell, and has undermined the wireline base to the point where AT&T might well exit a large proportion of it or perhaps sell off the division, refocusing on wireless, DirecTV satellite TV, and enterprise. At the moment, Comcast sees about 2 broadband net-adds for each triple-play net-add, although the increasing numbers of business ISP customers complicate the picture.

Source: STL, Comcast Q1 trending schedule

Since Christmas, the trend has picked up speed. Comcast announced a 2Gbps deployment to 1.5 million homes in the Atlanta metropolitan area, with a national deployment to follow. Time Warner Cable has announced a wave of upgrades in Charlotte, North Carolina that ups their current 30Mbps tier to 200Mbps and their 50Mbps tier to 300Mbps, after Google Fiber announced plans to deploy in the area. In the UK, Virgin Media users have been reporting unusually high speeds, apparently because the operator is trialling a 300Mbps speed tier, not long after it upgraded 50Mbps users to 152Mbps.

It is very much worth noting that these deployments are at scale. The Comcast and TWC rollouts are in the millions of premises. When the Virgin Media one reaches production status, it will be multi-million too. Vodafone-owned KDG in Germany is currently deploying 200Mbps, and it will likely go further as soon as it feels the need from a tactical point of view. This is the advantage of an upgrade path that doesn’t require much trenching. Not only can the upgrades be incremental and continuous, they can also be deployed at scale without enormous disruption.

This year’s CES saw the announcement, by Broadcom, of a new system-on-a-chip (SoC) for cable modems/STBs that integrates the new DOCSIS 3.1 cable standard. This provides for even more speeds, theoretically up to 7Gbps downlink, while still providing a broadcast path for pure TV. The SoC also, however, includes a WLAN radio with the newest 802.11ac technology, including beamforming and 4x4 multiple-input and multiple-output (MIMO), which is rated for gigabit speeds in the local network.

Even taking into account the usual level of exaggeration, this is an impressive package, offering telco-hammering broadband speeds, support for broadcast TV, and in-home distribution at speeds that can keep up with 4K streaming video. These are the SoCs that Comcast will be using for its gigabit cable rollouts. STMicroelectronics demonstrated its own multigigabit solution at CES, and although Intel has yet to show a DOCSIS 3.1 SoC, the most recent version of its Puma platform offers up to 1.6Gbps in a DOCSIS 3 network. DOCSIS 3 and 3.1 are designed to be interoperable, so this product has a future even after the head-ends are upgraded.

Source: RCRWireless

With multiple chipset vendors shipping products, CableLabs running regular interoperability tests, and large regional deployments beginning, we conclude that the big cable upgrade is now here. Even if cable operators succeed in virtualising their set-top box software, you can’t provide the customer-end modem nor the WiFi router from the cloud. It’s important to realise that FTTH operators can upgrade in a similarly painless way by replacing their optical network terminals (ONTs), but DSL operators need to replace infrastructure. Also, ONTs are often independent from the WLAN router or other customer equipment , so the upgrade won’t necessarily improve the WiFi.

The Broadcom device is so significant, though, because of the very strong WiFi support built in with the cable modem. Like the cable industry, the WiFi ecosystem has succeeded in keeping up a steady cycle of continuous improvements that are usually backwards compatible, from 802.11b through to 802.11ac, thanks to a major standards effort, the scale that Intel and Apple’s support gives us, and its relatively light intellectual property encumbrance.

802.11ac adds a number of advanced radio features, notably multiple-user MIMO, beamforming, and higher-density modulation, that are only expected to arrive in the cellular network as part of 5G some time after 2020, as well as some incremental improvements over 802.11n, like additional MIMO streams, wider channels, and 5GHz spectrum by default. As a result, the industry refers to it as “gigabit WiFi”, although the gigabit is a per-station rather than per-user throughput.

The standard has been settled since January 2014, and support is available in most flagship-class devices and laptop chipsets since then, so this is now a reality. The upgrade of the cable networks to 802.11ac WiFi backed with DOCSIS3.1 will have major strategic consequences for telcos, as it enables the cable operators and any strategic partners of theirs to go in even harder on the fixed broadband business and also launch a WiFi-plus-MVNO mobile service at the same time. The beamforming element of 802.11ac should help them to support higher user densities, as it makes use of the spatial diversity among different stations to reduce interference. Cablevision already launched a mobile service just before Christmas. We know Comcast is planning to launch one sometime this year, as they have been hiring a variety of mobile professionals quite aggressively. And, of course, the CableWiFi roaming alliance greatly facilitates scaling up such a service. The economics of a mini-carrier, as we pointed out in the Google MVNO: What’s Behind It and What Are the Implications? Executive Briefing, hinge on how much traffic can be offloaded to WiFi or small cells.

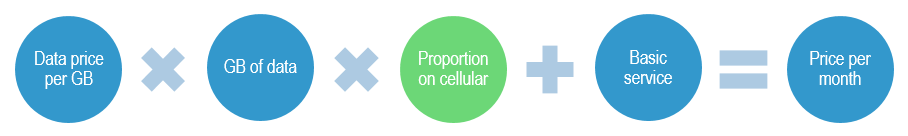

Source: STL Partners

Traffic carried on WiFi costs nothing in terms of spectrum and much less in terms of CAPEX (due to the lower intellectual property tax and the very high production runs of WiFi equipment). In a cable context, it will often be backhauled in the spare capacity of the fixed access network, and therefore will account for very little additional cost on this score. As a result, the percentage of data traffic transferred to WiFi, or absorbed by it, is a crucial variable. KDDI, for example, carries 57% of its mobile data traffic on WiFi and hopes to reach 65% by the end of this year. Increasing the fraction from 30% to 57% roughly halved their CAPEX on LTE.

A major regulatory issue at the moment is the deployment of LTE-LAA (Licensed-Assisted Access), which aggregates unlicensed radio spectrum with a channel from licensed spectrum in order to increase the available bandwidth. The 5GHz WiFi band is the most likely candidate for this, as it is widely available, contains a lot of capacity, and is well-supported in hardware.

We should expect the cable industry to push back very hard against efforts to rush deployment of LTE-LAA cellular networks through the regulatory process, as they have a great deal to lose if the cellular networks start to take up a large proportion of the 5GHz band. From their point of view, a major purpose of LTE-LAA might be to occupy the 5GHz and deny it to their WiFi operations.

To access the rest of this 14 page Telco 2.0 Report in full, including...

...and the following report figures...

...Members of the Executive Briefing Service and Future of the Network Stream can download the full 14 page report in PDF format here. Non Members, please subscribe here. For other enquiries, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

Technologies and industry terms referenced include: 802.11ac, Broadband, Broadcom, Cable, Comcast, DOCSIS3.1, Ethernet, fibre, fibre, infrastructure, TWC, WiFi.