|

Summary: Verizon and Comcast have invested in high bandwidth fibre and cable networks, whereas AT&T has until recently focused on U-Verse, an IPTV play. Which strategy is winning out and why? The answer is surprising and may transform the US and other markets, and there are parallels with Apple and Samsung’s ‘deep value’ strategies of investing in assets that are hard to replicate. (May 2014, Executive Briefing Service, Future of the Networks Stream). |

|

Below is an extract from this 21 page Telco 2.0 Report that can be downloaded in full in PDF format by members of the Telco 2.0 Executive Briefing service and Future Networks Stream here. We'll also be exploring the implications at the OnFuture EMEA 2014 Brainstorm in London, 11-12 June. For more on any of these services, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

To share this article easily, please click:

In this note, we compare the recent performance of three US fixed operators who have adopted contrasting strategies and technology choices, AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast. We specifically focus on their NGA (Next-Generation Access) triple-play products, for the excellent reason that they themselves focus on these to the extent of increasingly abandoning the subscriber base outside their footprints. We characterise these strategies, attempt to estimate typical subscriber bundles, discuss their future options, and review the situation in the light of a “Deep Value” framework.

Deep value strategies concentrate on developing assets that will be difficult for any plausible competitor to replicate, in as many layers of the value chain as possible. A current example is the way Apple and Samsung – rather than Nokia, HTC, or even Google – came to dominate the smartphone market.

It is now well known that Apple, despite its image as a design-focused company whose products are put together by outsourcers, has invested heavily in manufacturing throughout the iOS era. Although the first generation iPhone was largely assembled from proprietary parts, in many ways it should be considered as a large-scale pilot project. Starting with the iPhone 3GS, the proportion of Apple’s own content in the devices rose sharply, thanks to the acquisition of PA Semiconductor, but also to heavy investment in the supply chain.

Not only did Apple design and pilot-produce many of the components it wanted, it bought them from suppliers in advance to lock up the supply. It also bought machine tools the suppliers would need, often long in advance to lock up the supply. But this wasn’t just about a tactical effort to deny componentry to its competitors. It was also a strategic effort to create manufacturing capacity.

In pre-paying for large quantities of components, Apple provides its suppliers with the capital they need to build new facilities. In pre-paying for the machine tools that will go in them, they finance the machine tool manufacturers and enjoy a say in their development plans, thus ensuring the availability of the right machinery. They even invent tools themselves and then get them manufactured for the future use of their suppliers.

Samsung is of course both Apple’s biggest competitor and its biggest supplier. It combines these roles precisely because it is a huge manufacturer of electronic components. Concentrating on its manufacturing supply chain both enables it to produce excellent hardware, and also to hedge the success or failure of the devices by selling componentry to the competition. As with Apple, doing this is very expensive and demands skills that are both in short supply, and sometimes also hard to define. Much of the deep value embedded in Apple and Samsung’s supply chains will be the tacit knowledge gained from learning by doing that is now concentrated in their people.

The key insight for both companies is that industrial and user-experience design is highly replicable, and patent protection is relatively weak. The same is true of software. Apple had a deeply traumatic experience with the famous Look and Feel lawsuit against Microsoft, and some people have suggested that the supply-chain strategy was deliberately intended to prevent something similar happening again.

Certainly, the shift to this strategy coincides with the launch of Android, which Steve Jobs at least perceived as a “stolen product”. Arguably, Jobs repeated Apple’s response to Microsoft Windows, suing everyone in sight, with about as much success, whereas Tim Cook in his role as the hardware engineering and then supply-chain chief adopted a new strategy, developing an industrial capability that would be very hard to replicate, by design.

The biggest issue any fixed operator has faced since the great challenges of privatisation, divestment, and deregulation in the 1980s is that of managing the transition from a business that basically provides voice on a copper access network to one that basically provides Internet service on a co-ax, fibre, or possibly wireless access network. This, at least, has been clear for many years.

AT&T is the original telco – at least, AT&T likes to be seen that way, as shown by their decision to reclaim the iconic NYSE ticker symbol “T”. That obscures, however, how much has changed since the divestment and the extremely expensive process of mergers and acquisitions that patched the current version of the company together. The bit examined here is the AT&T Home Solutions division, which owns the fixed-line ex-incumbent business, also known as the merged BellSouth and SBC businesses.

AT&T, like all the world’s incumbents, deployed ADSL at the turn of the 2000s, thus getting into the ISP business. Unlike most world incumbents, in 2005 it got a huge regulatory boost in the form of the Martin FCC’s Comcast decision, which declared that broadband Internet service was not a telecommunications service for regulatory purposes. This permitted US fixed operators to take back the Internet business they had been losing to independent ISPs. As such, they were able to cope with the transition while concentrating on the big-glamour areas of M&A and wireless.

As the 2000s advanced, it became obvious that AT&T needed to look at the next move beyond DSL service. The option taken was what became U-Verse, a triple-play product which consists of:

This represents a minimal approach to the transition – the network upgrade requires new equipment in the local exchanges, or Central Offices in US terms, and in street cabinets, but it does not require the replacement of the access link, nor any trenching.

This minimisation of capital investment is especially important, as it was also decided that U-Verse would not deploy into areas where the copper might need investment to carry it. These networks would eventually, it was hoped, be either sold or closed and replaced by wireless service. U-Verse was therefore, for AT&T, in part a means of disposing of regulatory requirements.

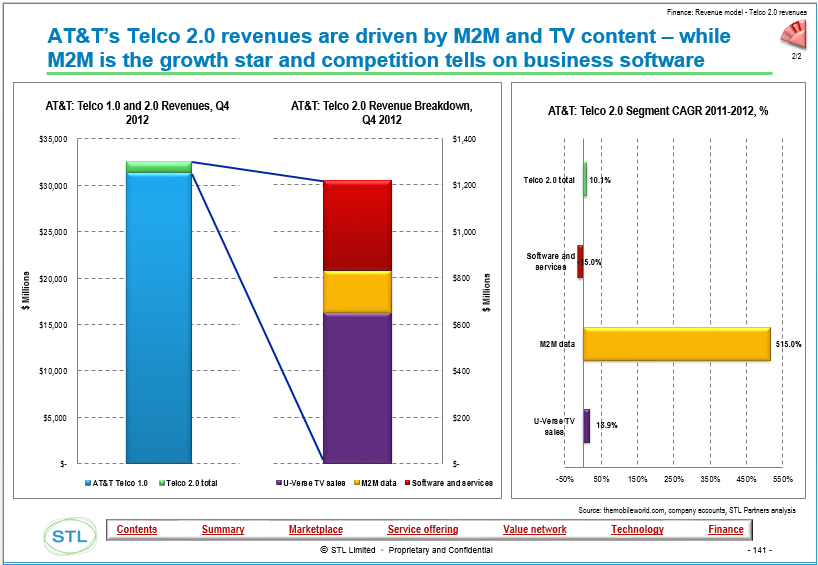

It was also important that the system closely coupled the regulated domain of voice with the unregulated, or at least only potentially regulated, domain of Internet service and the either unregulated or differently regulated domain of content. In many ways, U-Verse can be seen as a content first strategy. It’s TV that is expected to be the primary replacement for the dwindling fixed voice revenues. Figure 1 shows the importance of content to AT&T vividly.

Source: Telco 2.0 Transformation Index

This sounds like one of the telecoms-as-media strategies of the late 1990s. However, it should be clearly distinguished from, say, BT’s drive to acquire exclusive sports content and to build up a brand identity as a “channel”. U-Verse does not market itself as a “TV channel” and does not buy exclusive content – rather, it is a channel in the literal sense, a distributor through which TV is sold. We will see why in the next section.

It is well worth remembering that TV is a deeply national industry. Steve Jobs famously described it as “balkanised” and as a result didn’t want to take part. Most metrics vary dramatically across national borders, as do qualitative observations of structure. (Some countries have a big public sector broadcaster, like the BBC or indeed Al-Jazeera, to give a basic example.) Countries with low pay-TV penetration can be seen as ones that offer greater opportunities, it being usually easier to expand the customer base than to win share from the competition (a “blue ocean” versus a “red sea” strategy).

However, it is also true that pay-TV in general is an easier sell in a market where most TV viewers already pay for TV. It is very hard to convince people to pay for a product they can obtain free.

In the US, there is a long-standing culture of pay-TV, originally with cable operators and more recently with satellite (DISH and DirecTV), IPTV or telco-delivered TV (AT&T U-Verse and Verizon FiOS), and subscription OTT (Netflix and Hulu). It is also a market characterised by heavy TV usage (an average household has 2.8 TVs). Out of the 114.2 million homes (96.7% of all homes) receiving TV, according to Nielsen, there are some 97 million receiving pay-TV via cable, satellite, or IPTV, a penetration rate of 85%. This is the largest and richest pay-TV market in the world.

In this sense, it ought to be a good prospect for TV in general, with the caveat that a “Sky Sports” or “BT Sport” strategy based on content exclusive to a distributor is unlikely to work. This is because typically, US TV content is sold relatively openly in the wholesale market, and in many cases, there are regulatory requirements that it must be provided to any distributor (TV affiliate, cable operator, or telco) that asks for it, and even that distributors must carry certain channels.

Rightsholders have backed a strategy based on distribution over one based on exclusivity, on the principle that the customer should be given as many opportunities as possible to buy the content. This also serves the interests of advertisers, who by definition want access to as many consumers as possible. Hollywood has always aimed to open new releases on as many cinema screens as possible, and it is the movie industry’s skills, traditions, and prejudices that shaped this market.

As a result, it is relatively easy for distributors to acquire content, but difficult for them to generate differentiation by monopolising exclusive content. In this model, differentiation tends to accrue to rightsholders, not distributors. For example, although HBO maintains the status of being a premium provider of content, consumers can buy it from any of AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, any other cable operator, satellite, or direct from HBO via an OTT option.

However, pay-TV penetration is high enough that any new entrant (such as the two telcos) is committed to winning share from other providers, the hard way. It is worth pointing out that the US satellite operators DISH and DirecTV concentrated on rural customers who aren’t served by the cable MSOs. At the time, their TV needs weren’t served by the telcos either. As such, they were essentially greenfield deployments, the first pay-TV propositions in their markets.

The biggest change in US TV in recent times has been the emergence of major new distributors, the two RBOCs and a range of Web-based over-the-top independents. Figure 2 summarises the situation going into 2013.

Source: Telco 2.0 Transformation Index

The two biggest classes of distributors saw either a marginal loss of subscribers (the cablecos) or a marginal gain (satellite). The two groups of (relatively) new entrants, as you’d expect, saw much more growth. However, the OTT players are both bigger and much faster growing than the two telco players. It is worth pointing out that this mostly represents additional TV consumption, typically, people who already buy pay-TV adding a Netflix subscription. “Cord cutting” – replacing a primary TV subscription entirely – remains rare. In some ways, U-Verse can be seen as an effort to do something similar, upselling content to existing subscribers.

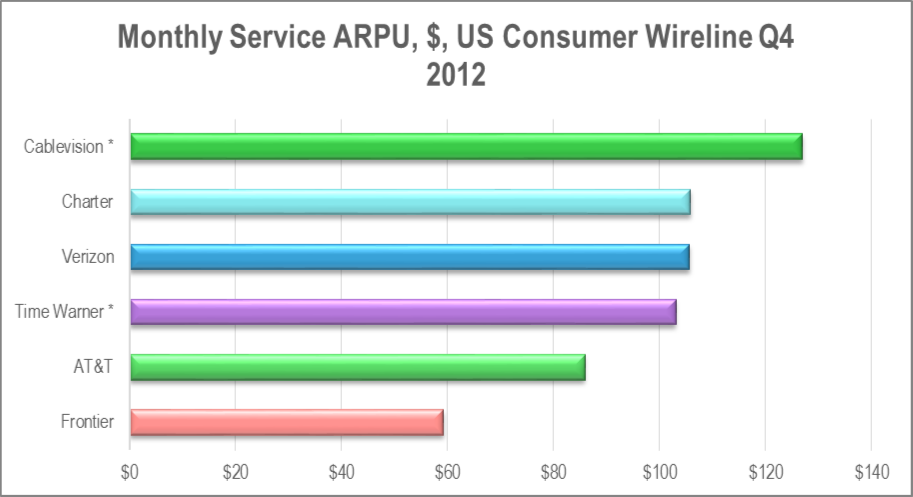

So how is this option doing? The following chart, Figure 3, shows that in terms of overall service ARPU, AT&T’s fixed strategy is delivering inferior results than its main competitors.

Source: Telco 2.0 Transformation Index

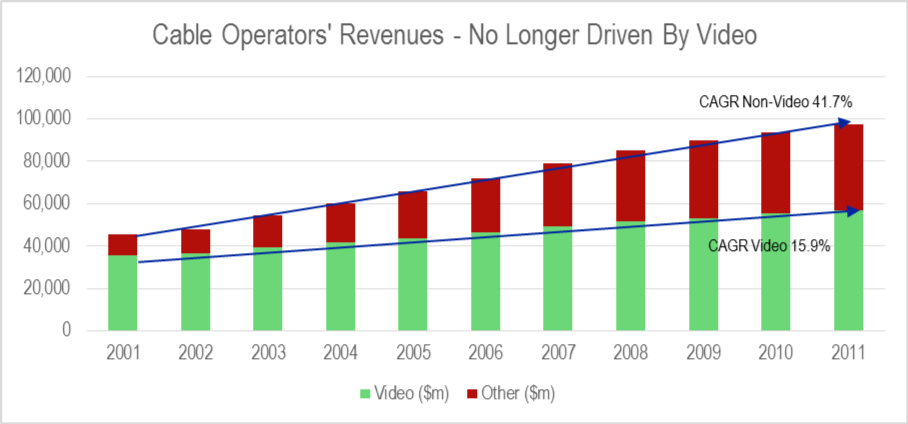

The interesting point here is that Time Warner Cable is doing less well than some of its cable industry peers. Comcast, the biggest, claims a $159 monthly ARPU for triple-play customers, and it probably has a higher density of triple-players than the telcos. More representatively, they also quote a figure of $134 monthly average revenue per customer relationship, including single- and double-play customers. We have used this figure throughout this note. TWC, in general, is more content-focused and less broadband-focused than Comcast, having taken much longer to roll out DOCSIS 3.0. But is that important? After all, aren’t cable operators all about TV? Figure 4 shows clearly that broadband and voice are now just as important to cable operators as they are to telcos. The distinction is increasingly just a historical quirk.

Source: NCTA data, STL Partners

Source: NCTA data, STL Partners

As we have seen, TV in the USA is not a differentiator because everyone’s got it. Further, it’s a product that doesn’t bring differentiation but does bring costs, as the rightsholders exact their share of the selling price. Broadband and voice are different – they are, in a sense, products the operator makes in-house. Most have to buy the tools (except Free.fr which has developed its own), but in any case the operator has to do that to carry the TV.

The differential growth rates in Figure 4 represent a substantial change in the ISP industry. Traditionally, the Internet engineering community tended to look down on cable operators as glorified TV distribution systems. This is no longer the case.

In the late 2000s, cable operators concentrated on improving their speeds and increasing their capacity. They also pressed their vendors and standardisation forums to practice continuous improvement, creating a regular upgrade cycle for DOCSIS firmware and silicon that lets them stay one (or more) jumps ahead of the DSL industry. Some of them also invested in their core IP networking and in providing a deeper and richer variety of connectivity products for SMB, enterprise, and wholesale customers.

Comcast is the classic example of this. It is a major supplier of mobile backhaul, high-speed Internet service (and also VoIP) for small businesses, and a major actor in the Internet peering ecosystem. An important metric of this change is that since 2009, it has transitioned from being a downlink-heavy eyeball network to being a balanced peer that serves about as much traffic outbound as it receives inbound.

The key insight here is that, especially in an environment like the US where xDSL unbundling isn’t available, if you win a customer for broadband, you generally also get the whole bundle. TV is a valuable bonus, but it’s not differentiating enough to win the whole of the subscriber’s fixed telecoms spend – or to retain it, in the presence of competitors with their own infrastructure. It’s also of relatively little interest to business customers, who tend to be high-value customers.

To access the rest of this 20 page Telco 2.0 Report in full, including...

...and the following report figures...

...Members of the Telco 2.0 Executive Briefing Subscription Service and Future Networks Stream can download the full 21 page report in PDF format here. Non-Members, please subscribe here. For other enquiries, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

Technologies and industry terms referenced include: TV, IPTV, content, cable, FTTH, broadband, FCC, regulation, deep value, strategy, bundling, AT&T, Comcast, Verizon, FiOS, U-Verse, network, infrastructure, Apple, Samsung, telecom, stratgies, transformation, business model.