Summary: Facebook, Google and others are pioneering the creation of the Personal Information Economy (PIE) based on consumer/user data. This Telco 2.0 analysis outlines emerging participants’ roles, and why, where and how telcos could and should play.

In this first of a series of briefing notes, Telco2.0 sets out to describe the potential roles for Telcos within the trust networks that we believe will underpin the future personal information economy. We'll also be discussing this at our AMERICAS, EMEA and APAC Executive Brainstorms and Best Practice Live! virtual events.

Personal Information – digital data relating to an identified or identifiable person – is being generated, transmitted and stored on a vast and increasing scale, primarily for internal use by organisations looking to better serve individuals, but increasingly for external use to support third-party organisations to better interact with those same individuals.

Still only a nascent industry, the business of using personal information to create value for individuals and income from third parties, holds considerable promise. For example, Facebook, only 6 years old and generating an estimated $1bn in revenues, somehow commands a $33bn valuation, by doing just this.

Personal Information Economics (PIE) isn’t just a new area for Telcos. It’s new for everybody, including individuals themselves and the regulators / legislators tasked with safeguarding personal freedom and privacy. Many disciplines cover aspects of PIE and the associated areas of Privacy and Identity (Law, Information Systems, Information Science, Economics, Public Policy, Psychology, Social Psychology, Philosophy) but few are geared to supporting those wishing to pursue it as a commercial practice. Subsequently, there are few frameworks to help Telco strategists and innovation practitioners to understand, communicate and quantify the opportunity.

For related Telco 2.0 analyses, please see 'World Economic Forum: Strategic Opportunities in Customer Data', the 'User Data & Privacy' and 'Adjacent & Disruptive' categories on the left-hand menu. These include 'Can telcos Unlock the Value of their Customer Data', and 'Google - where to compete, where to co-operate' and 'Facebook: moving into Telco Space?'.

For just about any on-line and off-line activity, the right personal information, automatically made available in the right way, could help to improve the experience, effectiveness, accuracy and cost of interactions. This applies to just about everything we do to participate in society and the economy: applying for a job, asking for advice, seeking a recommendation, evaluating goods and services, learning, giving, obtaining a quote, placing an order, making a payment, receiving goods and services, making a claim, checking past records, fixing a problem with an existing service or product. In fact, any system that allows parties to enter some form of transaction (even without any money exchanged) could benefit from trust networks that could somehow allow the right personal information to be shared systematically, in the right way.

Most current digital practices cannot support this:

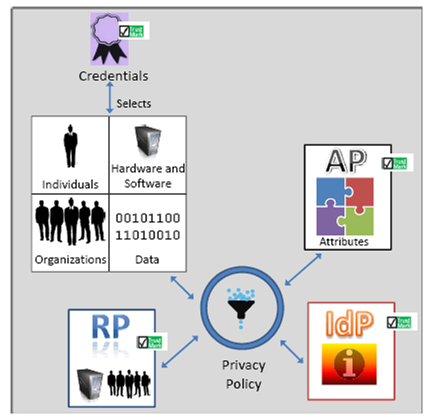

The term “trust networks” is used to describe a system that enables individuals to permit personal information (for example their age) held by one organisation, to be shared with another organisation. The diagram below illustrates some of the key roles operating in a trust network.

Figure 1 - Key Execution Roles in a Trust Network (Identity Ecosystem).

Source: NSTIC

The main roles identified by the US Dept. of Homeland Security’s National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC) are as follows:

An organisation could (and often does) fulfil more than one role in any given situation (e.g. identity providers are often also attribute providers).

The diagram does not include additional roles relating to the management and governance of the (potentially multiple) trust networks and the overall Identity Ecosystem under which they operate.

The NSTIC’s Identity Ecosystem Framework is a useful generic tool as it is applicable to a wide range of current off-line and on-line cases, including those involving public sector organisations (in multiple roles). Although it is primarily intended as a framework for interoperable identity to access online services, it provides a useful starting point for a broader personal information ecosystem that espouses a “user-centric” approach, by putting users at the heart of controlling their data.

The framework can be extended to cover marketing and advertising interactions as well as broader fulfilment interactions. Telco2.0 has provided the following to illustrate the range of possible applications:

The examples above illustrate three challenges with the broad principle that individuals should control the data validation and access management of their data:

1. In many situations (certain classes of data), the individual may be the subject of the data (for example on medical history or past driving offences) but that does not give them a right to alter the data (or even “how” the data is shared). The subject should be able to determine “if”, “when” and “to whom” their data is shared. Take driving offences. If an individual gives an insurance company access to driving offence history, then the individual cannot delete their history. If the individual chooses to hide something (presumably the most serious offences), the principle of user control supports that they should be able to do so, but the relying party then needs to be informed that the data is incomplete and also why it is incomplete (due to the subject’s instructions). The relying party can then reach their own conclusions about the individual’s application for insurance and quote them accordingly. All this has to be possible without even knowing who they are.

2. The ecosystem needs to include exchange mechanisms for individuals to draw benefit from sharing their data and providing permissions around how that data is then used. Many applications or service providers do allow individuals to trade permissions for functionality. Blyk is an example of this, since Blyk users sign-up to receiving targeted marketing conversations in exchange for service credits. Gmail provides another form of exchange: Gmail users benefit from an excellent email service in exchange for their outbound and inbound email being scanned for keywords prompting sponsored links to be presented (what makes Gmail even more remarkable is that users are free to access the service through an “ad-free” email clients such as Outlook or Gmail for Android).

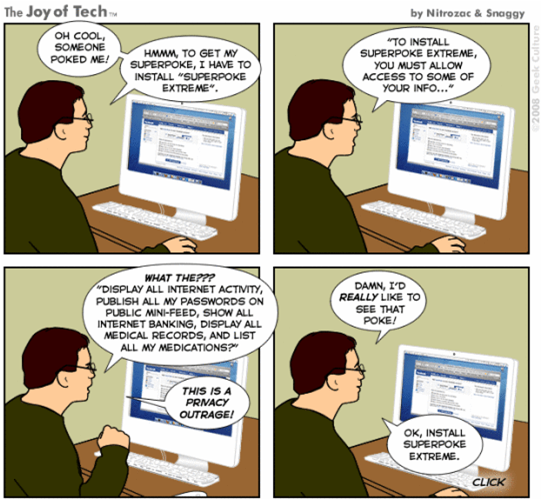

Figure 2 - A fair exchange?

Source: www.geekculture.com

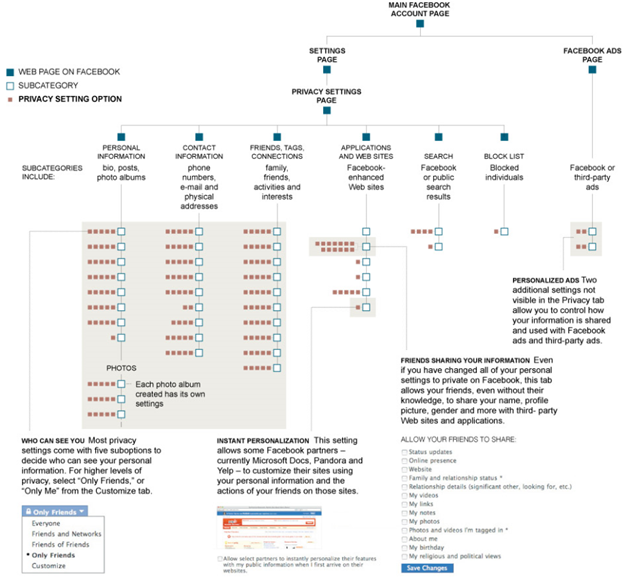

3. More can mean less when it comes to transparency and control. While the cartoon in Figure 2 illustrates the perils of over simplification, the Facebook example in Figure 3 shows that equally, having dozens of settings that one barely understands can create too much complexity for most users. This level of detailed control should be available, but there needs to be simpler visualisation of privacy settings that gives most users enough of an understanding of what they are permitting and how these permissions will play out (for example, which settings will mean that every request will be referred back for approval). Exactly how this visualisation works, could in itself allow identity providers to differentiate their services. This could even include allowing individuals to use pre-configurations, potentially posted by other users (i.e. “I recommend”), or dedicated organisations, or trusted brands, or even celebrities.

Figure 3 - In navigating Facebook’s privacy settings, it helps to have a map

Source: www.nytimes.com

To read the Analyst Note in full, including ...

...Members of the Telco 2.0TM Executive Briefing Subscription Service and the Dealing with Disruption Stream can download the full 12 page report in PDF format here (when logged-in). Non-Members, please see here for how to subscribe. Please email or call +44 (0) 207 247 5003 for further details.