|

Summary: In this extract previewing our upcoming report ‘Cloud 2.0: telco strategies in the Cloud’ we outline the three main groups of telco cloud strategies identified (Hunters, Gatherers and Innovators), and three future market scenarios (Cloud Layers, CloudBurst and CloudFail). (October 2012, Executive Briefing Service, Cloud & Enterprise ICT Stream.) |

|

For all enquiries, please email or call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

To share this article easily, please click:STL Partners has prepared a major Strategy Report on the cloud, Cloud 2.0: Telco Strategies in the Cloud, which covers the strategies of major telcos and their competitors from the Web 2.0 and enterprise IT industries, and forecasts market size into the 2020s. We intend to update our cloud coverage regularly in the coming years. This note is a sample of the larger research project, and an extract / preview of the Telco 2.0 presentations at the upcoming Digital Arabia and Digital Asia Executive Brainstorms (Dubai, 6-7th November and Singapore, 4th-5th December 2012).

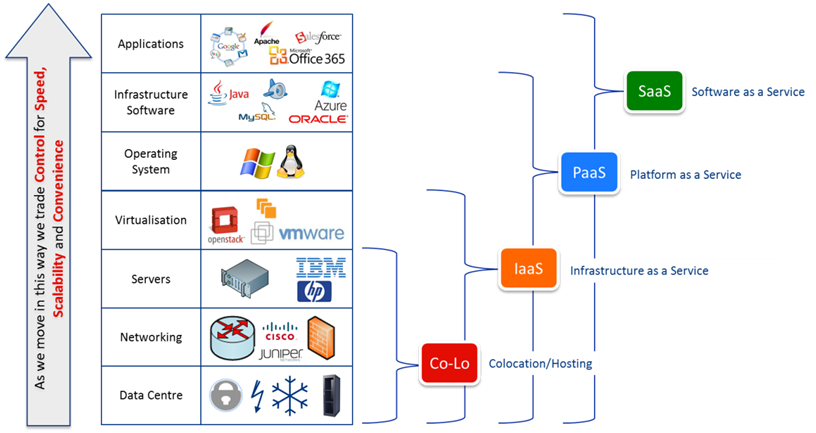

In the report, we are focusing on the core Enterprise Cloud product areas of Software-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), Virtual Private Cloud (VPC), and Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS). In Figure 1, we provide a reference to the layers in the “stack” of cloud products. The layers overlap and the distinctions between them are often blurred.

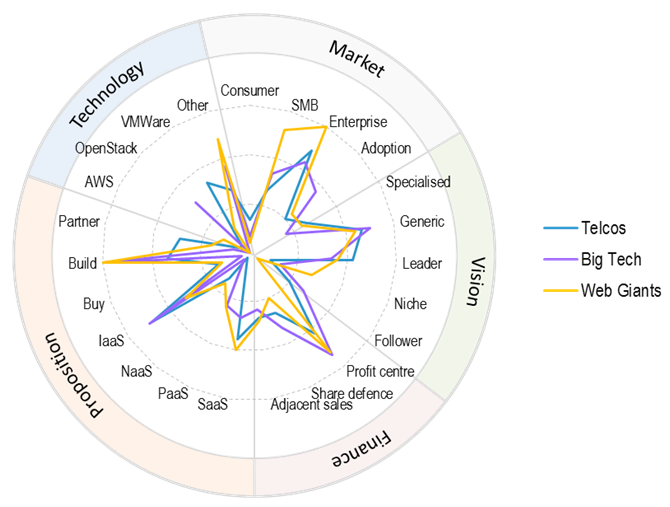

We assessed 10 major telcos (drawn from the Telco 2.0 Roadmap Report classifications “Large International”, “Regional”, and “Smaller National Leaders”) against a list of 30 criteria drawn from the categories “Market”, “Vision”, “Finance”, “Proposition”, “Technology”, and “Value Network” in the STL Partners business model framework.

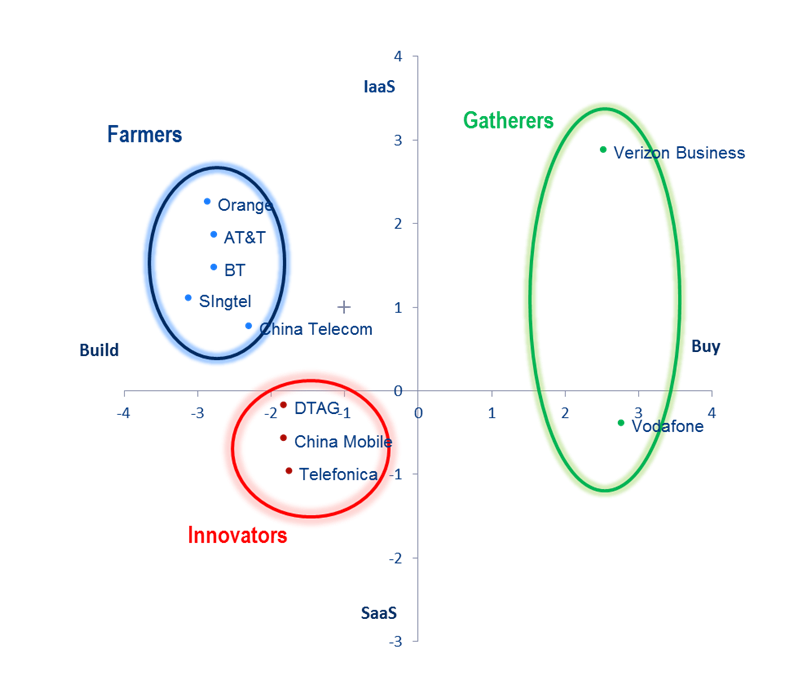

Reducing this data, we found that two of the most striking differentiators were the choice of an IaaS-heavy or SaaS-heavy strategy, and the decision whether to build or buy in cloud capabilities. Plotting our operators on these axes, we identified three clusters.

Figure 2: Telco Cloud cluster analysis

Source: STL Partners

The groups we identified are:

Across the telco sector, we found that in general, operators were inclining towards the “Farmers” or “Gatherers”, depending on their comfort or lack of it with big acquisitions. Typically, they hoped to target the enterprise sector, with general purpose IaaS offerings, and to deliver them from their own data centres once these were created. The following radar chart summarises the intentions of the telcos and their major rivals in this sphere that we also analyse in the report: the Web Giants (like Amazon Web Services) and Big Tech (like HP).

Source: STL Partners

The report contains an analysis of the strategies of the players outlined above, plus Elisa, Telstra, SFR and Belgacom, as well as the main technology players, plus recommendations on the key steps that telcos need to take to succeed in Cloud.

Looking forward, uncertainty is one of the constants in cloud, so we have envisaged three different possible scenarios of how the cloud market could play out (in addition to a core market forecast). These scenarios illustrate possible extremes and allow strategists to assess their reality or otherwise.

In this scenario, we envisage that certain problems, such as data sovereignty and compliance, resilience, geo-distribution, low latency, etc., can’t be solved by setting a different compiler flag. As a result, there is a substantial demand for more differentiated cloud services, specialising in the needs of particular industry clusters, applications, or geographies. This diversity permits a deeper level of cloud adoption overall – firms who could otherwise not have made use of it, because their particular needs weren’t adequately served – and contributes to a prosperous future.

The market structure evolves as follows.

This is a highly favourable scenario for telcos. For example, one UK-based operator might develop a specialised cloud service for the financial sector, offering low latency and guaranteed PCI-DSS compliance . Another telco might deploy distributed, modular data-centre pods around its network, sometimes getting as close to the user as their local street cabinet if space permits. This architecture would enable the telco to serve the media and gaming industries with extreme content delivery network (CDN) performance and snappy response times.

The key characteristics of this scenario include:

Some of these developments are already underway, such as the roll out of various national “G-Clouds” for governments.

In this scenario, a “category killer” dynamic, familiar from retailing, takes hold. The technical and commercial lead held by major IT and Web 2.0 players proves impossible to reverse. Economies of scale in the data centre business turn out to be even more extreme than previously thought, and projects of awe-inspiring size and ambition are common.

Large geographic areas, such as that around Prineville, Oregon, are transformed – the security and electrical requirements of such facilities tend to radically alter the landscape around them, which becomes marked by huge substations and eerily quiet setback zones. Cloud providers make extreme efforts to accommodate their customers’ requirements for greater control over their data, and integrate these options into their APIs and user tools. It is doubtful how real the data protection they offer actually is, but what matters is that all parties believe it to be effective.

Sub-scale hosting or cloud providers are either bought out, or else they go bust. In so far as the telcos have invested in cloud infrastructure, it’s a bruising experience for their shareholders.

However, those data centres need fibre. The key action from this scenario is that operators have to think about how they would win the contract to provide dark fibre and M2M out-of-band connectivity to (say) Facebook’s worldwide data centre infrastructure. Otherwise, the category killers will find it more useful to build their own – Google is a substantial investor in submarine cables. (Note, Facebook decided not to, and instead tapped TeliaSonera Carrier Services to manage its European network.)

A key characteristic of this scenario might be an exodus of developers from OpenStack, as running one’s own cloud or moving applications from a public cloud to a private cloud would be beside the point. This scenario might also involve an effort by Google to build up a customer-service capability supporting its products.

This scenario is simple: the cloud is actually a bubble, and it bursts.

This might happen through a combination of the following factors.

The key characteristics in this scenario might be a wave of “cloudfail”, the abandonment of several data centre megaprojects, and the emergence of traditional hosting products that approximate some features of the cloud. Although such an event would be an industry crash at least as spectacular as the .com bubble, telcos might not do so badly as they typically perform better in managed hosting than in cloud. The key action here would be “hang on to your hat”.

We believe that ‘Cloud Layers’ is the most likely scenario for the following reasons:

In Cloud 2.0: Telco Strategies in the Cloud, the upcoming Strategy Report, we dig deeper into the evolving market requirements and the key actions for operators, show much more detail on the key players in the cloud, and present a forecasting model for the future size and shape of the cloud market.

The opportunity is more than substantial, but it requires a much more “blue ocean” view of strategy, and substantial changes to service provider skills and channels to market. Otherwise, operators will be drifting into the world of “Gathering Stormclouds”, opposing an untried and sub-scale new business to their competitors’ A-team.

We'll also be exploring these issues further in the highly interactive Executive Brainstorm sessions at Digital Arabia in Dubai, 6-7 November, and Digital Asia in Singapore, 3-5 December. Please (including full contact details) if you’d like to register for these senior, invitation only brainstorms, or to pre-order your copy of the report.