|

Summary:

The Japanese and French markets have both been disrupted through the entry of low-cost competitors offering substantial price reductions. We think that Softbank’s acquisition of Sprint is a signal that the same is to soon come in the US given Softbank’s experience as a successful disruptor in Japan. (January 2013, Executive Briefing Service) |

|

Below is an extract from this 23 page Telco 2.0 Report that can be downloaded in full in PDF format by members of the Telco 2.0 Executive Briefing service here. Non-members can subscribe here or other enquiries, please email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.

We'll also be discussing our findings at the New Digital Economics Brainstorm in Silicon Valley, 19-20 March, 2013.

Japan used to be a mobile market with two serious competitors, high ARPUs and margins, and three laggard players that nobody took too seriously. France’s mobile market had three operators, a highly tolerant regulator, and high margins. And the US mobile market once had a relatively laissez-faire regulator, high ARPUs, two mighty duopolists, and two laggards.

The Japanese and French markets have both been disrupted through the entry of low-cost competitors offering substantial price reductions, and in Japan’s case the disruptor was Softbank. The US now has a regulator seemingly more influenced by voices from Silicon Valley than ‘big telco’ lobbyists, the duopolists have attractive margins, and Softbank now stands behind Sprint. The scene appears set for a disruptive play.

In Japan, back in 2006, when Vodafone sold its Japanese operation to Masayoshi Son’s Softbank, the mobile market was relatively stable with two large players – NTT Docomo and KDDI – and three much smaller ones including Softbank which were not making money (hence Vodafone’s decision to withdraw from Japan). Softbank spotted the disruptive possibilities of the Apple iPhone, the advantages of being Japan’s only operator on the UMTS world standard, and the fat margins of the duopolists. It became the iPhone exclusive carrier, benefited from world 3G infrastructure competition, and set keen prices on data to cut into the duopoly. And the results have been spectacular: Operating income has increased 6 times since Softbank acquired the business from Vodafone, and net additions in 2012 were running 127% higher than those of NTT DoCoMo and 51% higher than KDDI.

In France back in 2011, three French operators shared out the market, under the eyes of ARCEP, a regulator much more enthusiastic about planning for infrastructure development than driving competition. That year, Free.fr, a company that had already disrupted the fixed ISP market through mastering software and therefore having the best customer premises devices and the lowest costs, finally got a 3G licence. Using a radical new network design based on small cells and WLAN-cellular integration, Free tore into the oligopolists at staggeringly low prices.

In the United States, between 2005 and 2009, the friendly regulator – FCC Chairman Kevin J. Martin – permitted three great mergers in wireless, creating the new AT&T, the new Verizon, and the new Sprint-Nextel. Out of those, execution was successful in the first two. Sprint-Nextel misjudged the importance of Nextel’s specialism in voice, made a bad bet on WiMAX, leaving itself excluded from the emerging smartphone arena, and anyway had the hardest integration challenge. This is now acknowledged by Daniel R. Hesse, Sprint-Nextel’s CEO.

"Hesse said that the AT&T’s failed attempt to consolidate two of the Big 4 made him realize that there was no longer such a thing as the Big 4. The industry had bifurcated into the Big 2 and everybody else." ... “With 20/20 hindsight, the Nextel merger was a mistake,” Hesse said. “The synergies, if you will, that we had hoped for and planned for didn’t materialize.”

Source: GigaOm

AT&T and Verizon, however, made it across the merger swamp to found an effective duopoly, a dominating force that controls 68% of revenue in the world’s critical wireless market, and which regularly achieves 30+% margins while its rivals struggle to break even. Verizon’s decision to end the standards wars and go with LTE effectively killed the CDMA development path and left Sprint stuck with WiMAX. Was it strategy or happy accident?

Now, things have changed. Sprint has been bought out by none other than Softbank – the original Japanese disruptor. It is a reminder that strategic advantage is temporary and disruption is inevitable.

We expect that the new Sprint will take the pain to push ahead with its transition to LTE. The previous Softbank and Sprint experiences have shown that being outside the world standard is deadly from a devices point of view, which remains critical to success in mobile. We expect that they may make a much bigger effort with carrier WLAN, far better standardised, far more available, and in many ways technically more robust than WiMAX.

We also expect that Sprint/Softbank will aim for the simplest form of disruption, price war. Oligopolies are always either in a state of price stability or of price war. Whether a cartel controls the market, or a tacit balance of fear constrains action, stability reigns, until it doesn’t. Then, price war rages, as no-one can afford to resist. Customers will benefit. T-Mobile, trying to fight its way to the start-line, will suffer most of all.

Another lesson from Softbank, though, is that disruption on price needs a killer product if it is to be more than a race to the bottom. We explore some further strategy options for Sprint in the body of this report.

In addition to its impact on the core US telecoms market, the prospect of forthcoming disruption also raises the stakes on the question of whether the US telcos are transforming to new Telco 2.0 business models fast enough (see our report A Practical Guide to Implementing Telco 2.0). This is a topic that we will explore further in our research and at the next Silicon Valley Executive Brainstorm, March 19-20, 2013.

Masayoshi Son’s strategy at Softbank, after acquiring the Vodafone stake, was simple – sharp pricing, especially on data, and hot gadgets.

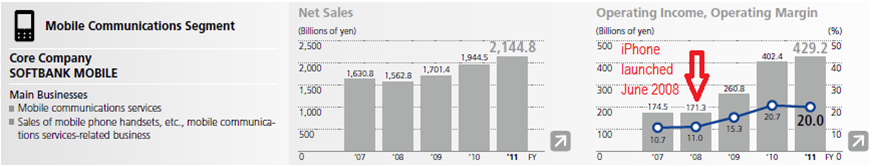

Softbank was the launch partner for the iPhone in Japan and remained Apple’s exclusive carrier up to the release of the iPhone 4S. Softbank’s annual report shows the impact of the iPhone and repricing very clearly – the partnership with Apple was signed in June, 2008, and the iPhone 4S launch followed in Q3 2011. The disruption was transient, but it had lasting effects on the market, restoring Softbank as a serious competitor, in much the same way as it turbocharged AT&T in the US a year before.

Figure 1: iDisrupt – the June ‘08 iPhone launch reset the market in Japan

Source: Softbank

Source: Softbank

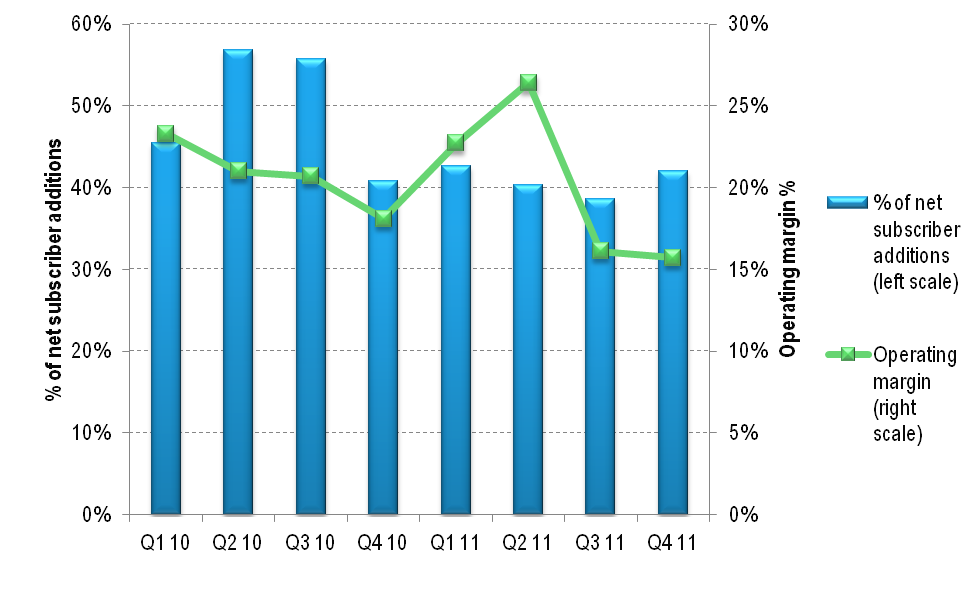

The combination of keen pricing and iPhones had a lasting effect on subscriber growth, too. Throughout the exclusivity era, Softbank beat its rivals for net-adds handsomely.

However, this came at a price. On a quarterly basis, a steady erosion of operating margin is visible, driven partly by the pricing strategy and partly by the cost of the shiny, shiny gadgets. One way of mitigating this was to carve out the cost of the device from the cost of service. Rather than paying nothing up front, Softbank subscribers paid a monthly device charge, or else either paid cash or brought their own.

Softbank’s annual report says that their subscriber-acquisition cost was falling in their FY 2012 (i.e. 2011-12), but also that the average subscriber upgrade cost had increased – in a smartphone environment, users who were brought on board on a cheaper device will tend to eventually demand something better.

As a result, Softbank has been able to keep its share of net adds over 40%. In a market with four players, this is a major achievement. However, to do so, they have had to accept the erosion of their margins and pricing.

Figure 3: Softbank - keeping ahead of the competition…

Source: STL Partners, Softbank

Source: STL Partners, Softbank

Clearly, price disruption can work, and it is reasonable to think that something similar might happen in the US, a similar market. In the international context, US mobile operators are pricey: the US is the fourth-highest OECD market by ARPU.

On average, for instance, a triple-play package that bundles Internet, telephone and television sells for $160 a month with taxes. In France the equivalent costs just $38. For that low price the French also get long distance to 70 foreign countries, not merely one; worldwide television, not just domestic; and an Internet that’s 20 times faster uploading data and 10 times faster downloading it.

To read the note in full, including the following additional analysis...

...Members of the Telco 2.0 Executive Briefing Subscription Service can download the full 23 page report in PDF format here. Non-Members, please subscribe here or email / call +44 (0) 207 247 5003.